Companies prosper because they offer to the market an authentic value proposition; companies then suffer because they extend to the market an increasingly diluted value proposition.

— Flint McGlaughlin, Managing Director and CEO, MECLABS Institute

For decades, Radio Shack was one of America’s most trusted and beloved brands. It was a place where DIYers sought parts and advice, where the brightest minds gathered to share ideas and where the latest in technological innovation was showcased. Radio Shack was a mecca for tinkerers looking for that specific part, students looking for science project materials and tech enthusiasts looking for cutting-edge products.

Now, the once-beloved retailer has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection after losing nearly a billion dollars since late 2011. Prior to the filing, capital was stretched so thin that the company couldn’t even afford to close its 1,000 lowest performing stores.

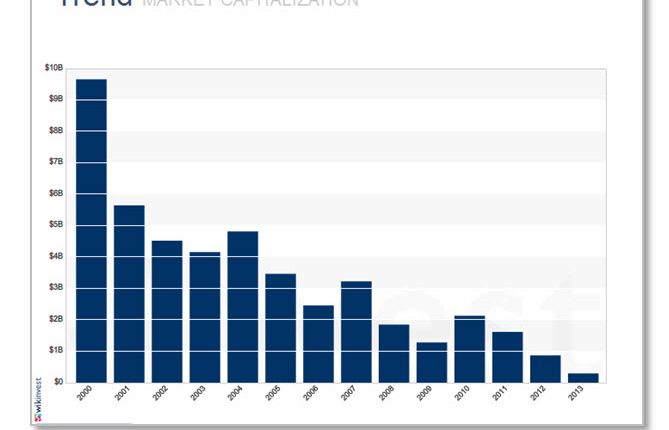

Radio Shack’s stock (RSHCQ) was delisted by the New York Stock Exchange in early February after losing 90% of its value in the last year, tumbling as low as $0.09 per share from a high of $76.77 in 1999.

By the end of March, 1,784 of Radio Shack’s 7,100 stores will close, and companies like Sprint, Gamestop and Amazon are already circling overhead, ravenously waiting to pick at the bones of this once-iconic company.

Meanwhile, Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Kilmartin has issued an urgent warning to his constituents, pleading with them to spend their Radio Shack gift cards as quickly as possible.

How did things go so wrong for this company?

And how did Radio Shack, a company that once had a market capitalization of over $15 billion, fall so mightily that it is now in the process of auctioning off its name for a mere $20 million?

The answer is simple:

By turning its back on its authentic value proposition, foregoing specificity for generality and neglecting the legacy customer that had historically facilitated Radio Shack’s success.

A brief history of Radio Shack

In 1921, Theodore and Milton Deutschmann went into the audio business. The two brothers named their one-store retail and mail-order operation “Radio Shack” after the small, wooden structures used to house radio equipment inside ships. True to the name, their merchandise consisted mostly of radio and audio hardware that was primarily aimed at naval officers stationed in Boston Harbor.

Customers Test Audio Equipment at Radio Shack (1931) (source: PC World)

Though Radio Shack would survive the Great Depression and open several more stores in Boston in the coming decades, its primary story begins in the early 1960s when a hobbyist named Charles Tandy saved the company from bankruptcy.

The Tandy family had been in the leather business for decades, but when Charles took over for his father, he began shifting Tandy Leather’s marketing focus from general leather goods into the highly-specific hobby market.

Before long, scouts and campers from all over the country were making wallets, coin purses, moccasins and other items using Tandy leathercraft hobby kits. Under Charles Tandy’s direction, the family leather business became so successful that it began trading on the New York Stock Exchange in 1960.

Looking to diversify, Tandy purchased Radio Shack in 1963. At the time, Radio Shack consisted of nothing more than nine failing retail locations in Boston. The company was on the verge of bankruptcy, with nearly a million dollars in uncollected debt and tens of thousands of products that no one was particularly interested in purchasing.

Diluting the value prop

Though the chain had found success in the 1940s and early 1950s, its decline corresponded with a shift in focus from selling several hundred specialized products to highly-specific professional and amateur radio enthusiasts to peddling a bloated inventory of nearly 25,000 items to anyone willing to buy them. Ironically, it was this same dilution of value proposition that would ultimately doom the company a half-century later.

Forging a business plan

Specificity converts. Indeed, for any reasonable sample size, the specific offer to the specific person will outperform the general offer to the general person.

— Flint McGlaughlin

Charles Tandy purchased Radio Shack with the intention of returning it to its roots. Like all great marketers, Tandy knew exactly who his ideal customer was, as evident by his simple statement of purpose for the company:

Appeal to hobbyists

As Bloomberg Business Week writes:

Tandy described the ideal Radio Shack customer to a group of financial analysts. ‘We’re not looking for the guy who wants to spend his entire paycheck on a sound system.’ Instead, he went after customers looking to save money by buying cheaper goods and improving them through modifications and accessorizing. The target audience was people who needed one small piece of equipment every week.

Super-serving the specific Tandy Leather customer ultimately resulted in the company being listed on the New York Stock exchange, and Charles was confident that the same business model would work for Radio Shack. Selling the right product mix, with the right frequency, to a highly-specific customer would be key to Radio Shack’s long-term health and growth.

With a clear understanding of who his key customer was, Tandy developed Radio Shack’s initial business model on the back of several key tenets.

1. Product turnover is key. Rather than engage in a race to the bottom on pricing with his competitors, Tandy instead maintained market prices but cut Radio Shack’s previous inventory of 20,000 items down to only the 2,500 items with the highest sell-through rate. The change resulted in a high rate of product turnover, lower operating costs and soaring gross profit.

2. Gross profit margins are vital. To keep prices competitive, Tandy primarily stocked private label items, either manufactured through exclusive contracts with manufacturers or by the Tandy Corporation itself. This cut out the middleman. Within 30 years of Tandy’s takeover, Radio Shack would have 31 plants throughout the world, manufacturing batteries, soldering irons, microchips, capacitors, wire, etc. for Radio Shack stores. By keeping production in-house, Radio Shack was able to maintain a staggering +50% gross profit margin on retail sales.

Private Label Radio Shack Batteries

3. Marketing is everything. Tandy often said that, “If you want to catch a mouse, you have to make a noise like a cheese.” 10% of Radio Shack’s gross profits routinely went into marketing, whether it be mass marketing via sensationalistic newspaper ads and flyers or targeted marketing, via tech and hobby publications.

4. A knowledgeable, motivated sales staff is worth its weight in gold. Tandy believed that in order for Radio Shack to be a success, knowledgeable staff had to be hired, and they had to be given a financial stake in the company’s success. This “institutionalized entrepreneurship” resulted in successful employees earning up to ten times their salary through bonuses and profit sharing. 60 employees eventually became millionaires as the result of this policy.

5. Strategic risk-aversion protects the bottom line. Tandy felt it was vital to be on the cutting edge of technology, but he also believed in strategic risk-aversion. When new technology emerged, Tandy often let other retailers act as guinea pigs, while he quietly gauged market interest from the side. If a product appeared on the verge of catching fire, Tandy would quickly divert his manufacturing resources toward creating a Radio Shack private label brand of the product, put his full advertising force behind it and capture a large portion of the market virtually overnight.

Scene from Radio Shack in the 1960s (source: PC World)

Becoming a neighborhood institution

People do not buy from companies; people buy from people.

— Flint McGlaughlin

Tandy’s vision took form through a collection of small stores, staffed by experts in electronics, selling a specialized assortment of popular, high-margin merchandise to hobbyists.

The results of his business plan were incredible.

Less than two years after being acquired by Tandy for $300K ($2.3M in 2015 USD), Radio Shack was turning a profit. Within a decade, the chain had grown from eight stores to over 1,000, with two new locations opening every day.

In a short time, Radio Shack was no longer a mere store, but a neighborhood institution where ideas and knowledge were discussed and disseminated. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak were regular customers, purchasing transistors and diodes to assist with their tinkering. Stores were staffed by knowledgeable, trustworthy sales clerks, eager to talk shop or provide advice to customers about anything from setting up a stereo to building a primitive robot. In fact, many employees actually started out as loyal customers.

Radio Shack even began a free “Battery of the Month” club, entitling each card holder to a free battery per month. This inexpensive loss leader gave customers an added incentive to return to the store regularly, even if they didn’t need advice or cables to set up their stereos.

In the words of Bloomberg, “Nerds ate it up.”

As the 1970s began, Radio Shack was practically printing money.

Charles Tandy transformed a bankrupt Boston electronics chain into a national juggernaut, all on the strength of a bulletproof value proposition formed by thinking his way into the thinking of his ideal customer.

As marketers, we know that the strongest value propositions are forged by looking at our business through the eyes of our customer and asking ourselves one simple question: If I am your ideal prospect, why would I buy from you rather than any of your competitors? The best answers come in the form of a “Because … ” statement, strong in appeal, exclusivity, credibility and clarity.

Charles Tandy had a powerful answer for this value proposition question:

“Because Radio Shack stores provide specialized, innovative parts and merchandise not available anywhere else, sold by the most tech-knowledgeable staff in retail.”

By honoring this core value proposition, Radio Shack was untouchable. Tandy could barely open stores fast enough to meet demand. But, as we’ll see in part two, when this value prop began to erode, so did Radio Shack.

Be sure to watch for parts two and three of this dive into value proposition in upcoming MarketingExperiments Blog posts.

You can follow Ken Bowen, Manager of Partner Content, MECLABS Institute, on Twitter at @KenBowenJax.

You might also like

Value Proposition: How to turn a shiny new value proposition into a high-performing page [MarketingSherpa webinar archive]

Marketing Optimization: 4 steps to discovering your value proposition and boosting conversions [More from the blogs]

Marketing Research Chart: Is value proposition testing part of your lead gen strategy? [MarketingSherpa chart]

Value Proposition: Between perception and reality [More from the blogs]