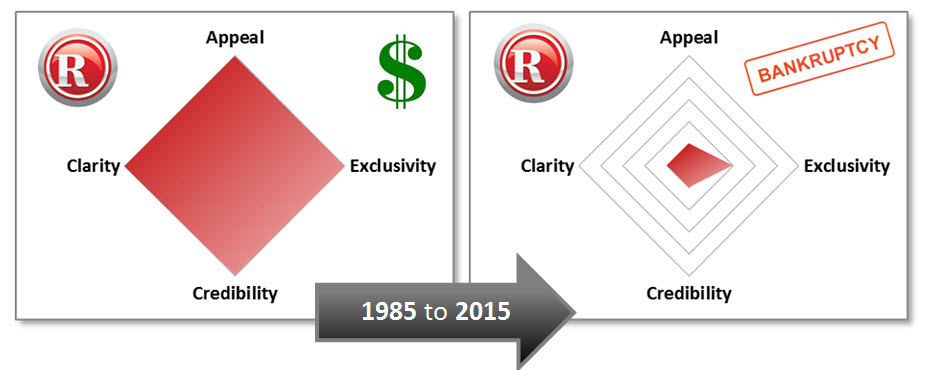

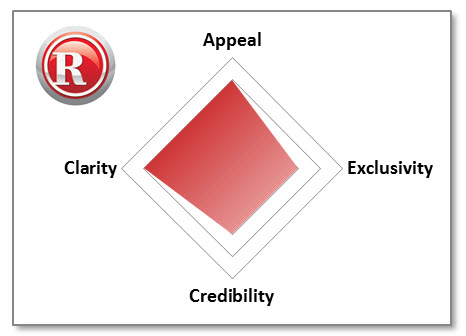

As marketers, Radio Shack should serve as an important cautionary tale of how quickly our businesses can erode if we lose sight of our core value proposition. The first two parts of this three-part blog series (read part one here and part two here) documented Radio Shack’s meteoric rise to retail prominence throughout the 1960s and 70s, accomplished by identifying the ideal customer (the hobbyist) and offering to the market a unique, authentic value proposition built upon a foundation of four key factors:

Credibility — Can I trust your claims?

Clarity — What are you actually offering?

Exclusivity — Can I only get this from you?

Appeal — How much do I desire this offer?

By honoring this core value prop — Radio Shack stores provide specialized, innovative parts and merchandise not available anywhere else, sold by the most tech-knowledgeable staff in retail — Radio Shack grew from a handful of bankrupt Boston electronics stores to a retail juggernaut with more storefronts than McDonalds.

The mid-1980s would mark the beginning of the end for Radio Shack, as the company continuously diluted, rather than refined, the comparative strengths of the exclusivity, appeal, credibility and clarity that served as the bedrock for its core value proposition.

The Mid-1980s — Marginalizing the core customer

Who is your customer? How did that customer find you, and why did he buy from you? What does that customer tell others about you? Even more important, what does the customer wish your company would do for him? That knowledge is your only true source of power.

— Kristin Zhivago, Revenue Coach, Author of Roadmap to Revenue: How to Sell the Way Your Customers Want to Buy

By 1984, even though Radio Shack’s stores continued to stock parts and components popular with hobbyists, the company’s specific focus on the DIY market was clearly beginning to shift.

The success of the TRS-80 had given Radio Shack a sense of arrogance, and the company began claiming that small businesses and schools were Radio Shack’s new target market, rather than hobbyists, who were “not the mainstream of the business.” This pinched-nose approach to hobbyists would pervade Radio Shack’s messaging for the next 30 years, whether explicit or implicit.

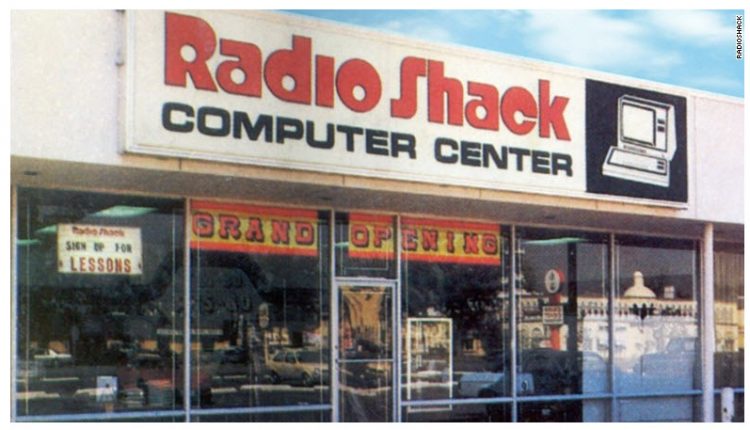

In fact, hundreds of neighborhood Radio Shack stores saw products aimed at the hobbyist and tinkerer disappear entirely when the stores were converted into Radio Shack Computer Centers.

Ironically, these hobbyists that Radio Shack alienated were among the earliest adopters for new technology, including the TRS-80, and many were quickly growing frustrated with some of Radio Shack’s practices.

Although Tandy’s computers boasted superior hardware performance to competitors — often running up to three times faster than its IBM counterparts — the software library for Radio Shack’s line of personal computers was not nearly as robust as IBM or Apple’s.

Because of the company’s insistence on offering mostly private-label products, the TRS-80 computer was designed to work primarily with inferior Radio Shack-brand software. In the absence of MS-DOS, largely superior IBM-compatible software was not compatible with the TRS-80.

Further, expensive peripherals that customers bought for the TRS-80 were purposely designed to be incompatible with other personal computers.

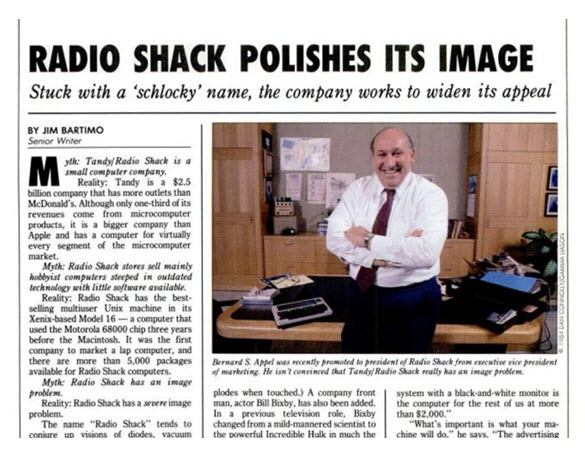

Tech enthusiasts, who historically drove most of Radio Shack’s business, were incensed by the company’s stubbornness and began referring to the TRS-80 as the “Trash-80.” The derisive nickname caught on in the media, and for the first time in its history, Radio Shack had a serious image problem on its hands.

In fact, Radio Shack lost so much brand equity during this period that the Tandy Corporation had to remove Radio Shack branding entirely from its computer line.

Ron G. Stegall, Senior Vice President for Computer Marketing at Radio Shack told InfoWorld magazine in a 1984 cover story, “We took the Radio Shack name off the Tandy computer because we were told by customers that the Radio Shack name was a problem in the office.”

By 1985, Radio Shack’s market share for personal computers had fallen from a high of nearly 20% to less than 9%, never to recover.

Even as the stock market at large began to emerge from the recession, Wall Street brokerage firms viewed Tandy/Radio Shack’s stock bearishly, recommending that investors sell their shares for the first time since Tandy had gone public.

For eight more long years, Tandy/Radio Shack would fight a losing battle for PC market share, diverting valuable resources from the company’s core goal established by Charles Tandy 30 years prior: appeal to hobbyists.

By 1993, with its competitors outpacing it in both price and performance, Radio Shack finally disbanded its PC division and stopped producing personal computers altogether.

Unfortunately, the damage had already been done. By marginalizing the hobbyists, confusing the marketplace and stubbornly refusing to offer basic IBM compatibility for its machines, Radio Shack had lost a portion of the exclusivity, appeal, credibility and clarity that had made them so successful in the past.

Late 1980s Radio Shack — Value Prop Radar Chart

The Mid-1990s — Further diluting the value proposition

In the mid-90s, Radio Shack made the baffling decision to become a big-box retailer. More specifically, the company planned to become the biggest box in consumer electronics.

Even though Radio Shack was on the path to bankruptcy in the early 1960s before being purchased by Charles Tandy for this very reason, Radio Shack would again attempt to be the retailer that sold everything to everyone. This plan would be realized through several chains of egregious mega-stores, the most notable being Incredible Universe.

Incredible Universe could not possibly be any more different than the small neighborhood stores selling high-margin merchandise to the highly specific customer that Radio Shack had built its success upon. Each Incredible Universe store featured tens of thousands of items, including 342 models of televisions, 72 types of VCRs, 48 computers, 580 appliance models and hundreds of cameras. Stores contained restaurants, karaoke recording studios, a disc jockey and even arcades.

Each Incredible Universe was so large that Radio Shack needed $100 million in annual sales per store just to break even.

Incredible Universe Commercial

Although Radio Shack’s revenue peaked in 1996 on the back of Incredible Universe, the massive operating costs left the company with its first annual loss in decades. Within a year, Radio Shack was out of the big-box business, and the strength of its once-authentic value proposition had been further eroded.

Mid 1990s Radio Shack — Value Prop Radar Chart

The Early 2000s — Abandoning the authentic value proposition

After disbanding its PC division and abandoning the big box, Radio Shack had a golden opportunity to shift its focus back to the authentic value proposition that Charles Tandy had established for the company when he purchased it in 1963.

Hobbyists and electronic enthusiasts were still in abundance, perhaps even growing in number due to the tech boom, and Radio Shack enjoyed a competitive advantage with these customers through exclusive, specific merchandise and best-in-class customer service.

Instead of recommitting to the ideal customer, Radio Shack once again went looking for a silver bullet.

Mobile phones were still in their infancy, and carriers were eager to be the first to get the expensive handhelds (and expensive telephone plans) into the hands of consumers. So eager, in fact, that they were willing to cut sweetheart deals with Radio Shack. Not only would Radio Shack receive an upfront commission on each cell phone sold, but they would also receive a cut of the monthly bill.

Radio Shack decided to go all in on mobile.

Early Radio Shack Cell Phone Commercial

When speaking with Bloomberg, a former Radio Shack executive compared the wireless business to a narcotic, with the company bingeing on phone sales while ignoring its core business. Pushing mobile phones at the expense of nearly everything else is, in this writer’s opinion, what sowed the seeds for the company’s ultimate demise.

The primary victim of this mobile-centric strategy was Radio Shack’s reputation for great customer service. The knowledgeable, tech-savvy sales clerks that customers had come to rely on were replaced with aggressive cellphone salesmen.

A single cell-phone transaction often took up to 45 minutes to process, and Radio Shack’s ideal customers often left the store in frustration when the sales staff was either incapable of answering its tech-related questions or too tied up to lend support. As a result, foot traffic decreased dramatically at Radio Shack stores.

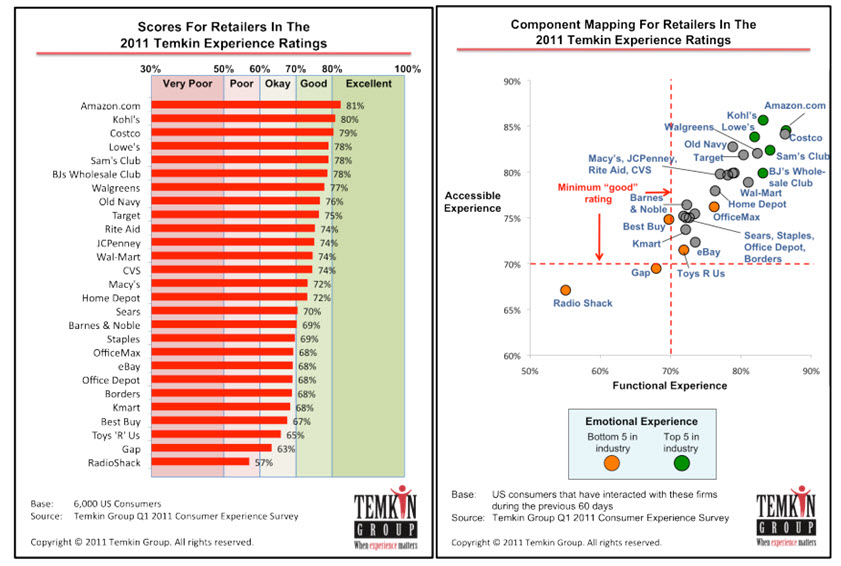

Radio Shack’s once-celebrated customer service eroded so badly as a result of the mobile-focus that in recent years, the company is routinely ranked as worst-in-industry by a wide margin.

Where once Radio Shack had the most trusted employees in America, Radio Shack now employs what retail expert Warren Shoulberg calls, “the most intimidating, least-female shopper friendly and all-in-all scary collection of people ever assembled by one corporate entity.”

Radio Shack Named Worst-in-Class for Customer Experience (Temkin Group, 2011)

The beginning of the end

Any attempt to articulate a value proposition that does not communicate more net value than the competitor’s is insufficient.

— Flint McGlaughlin, Managing Director and CEO, MECLABS Institute

Early 2010s Radio Shack — Value Prop Radar Chart

Radio Shack limped forward into the 21st century, with margins on cell phone sales growing smaller and smaller as carriers opened their own stores and the market began to reach saturation. Profit turned to breaking even, and breaking even turned to staggering loss.

Company executives came and went through present day, sticking around just long enough to introduce goofy new marketing campaigns that did little to strengthen Radio Shack’s authentic value proposition, let alone differentiate then from the competition.

Numerous new taglines were introduced, including:

“Radio Shack: Let’s play!”

“You’ve got questions, we’ve got answers.”

“It Can Be Done, When We Do It Together”

“Our Friends Call us the Shack”*

*“With friends like that,” online brand consultant UnderDesign joked, “who needs enemies?”

While competitors beefed up their ecommerce business, Radio Shack’s long-ignored online presence actually found a way to contract by 20% since 2003.

Though consumer electronics is historically one of the biggest, most profitable ecommerce categories, Radio Shack’s online business almost inconceivably accounts for only 1% of total sales. In March 2014, brand spokeswomen Merianne Roth stated, almost comically, “We plan to leverage online more. We have plans for later this year.”

25 years of Radio Shack’s missteps have finally came to roost early this year, and by the time that bankruptcy proceedings are complete, Radio Shack as America has known it for over 50 years will likely cease to exist entirely.

As marketers, it is important that we understand what went so badly wrong for Radio Shack and how we can avoid repeating the same mistakes of Charles Tandy’s predecessors.

Lessons learned

Companies prosper because they offer to the market an authentic value proposition; companies then suffer because they extend to the market an increasingly diluted value proposition.

— Flint McGlaughlin

As marketers, there are valuable lessons that we can learn from the rise and fall of one of America’s great retailers.

First and foremost, we must always remember that doing the right thing is more important than doing the thing right.

In Radio Shack’s case, doing the right thing meant appealing to hobbyists, emphasizing world-class customer service and being a front-runner in new technology. When Radio Shack put its full weight behind that exclusive, authentic value proposition, profits soared.

But when Radio Shack diluted that core value proposition by pushing out hobbyists and shifting its inventory from highly-specific merchandise aimed at the ideal customer to the same mass-market consumer electronics found in a million other stores, the bottom fell out.

Numerous times, Radio Shack had the opportunity to correct its course. Had executives stopped trying to compete with the Best Buys of the world (any attempt to articulate a value proposition that does not communicate more net value than the competitor’s is insufficient) and instead focused on the thinking of its ideal legacy customer, Radio Shack could still be thriving today.

In recent years, the DIY trend has made an incredible resurgence. People are more inclined than ever to be building their own PCs. Lego has experienced tremendous year-over-year growth, particularly with its Technic line. Crowd-funding sites like Kickstarter have put capital at the fingers of tinkerers, resulting in products such as the Pebble smartwatch, COOLEST beverage cooler and OUYA video game console, all of which were prototyped with off-the-shelf parts.

Instead of looking like a dated Sprint store, Radio Shack could have once again become a vibrant place where ideas were shared. A place to learn about, buy or build bleeding-edge technology like 3D printers, drones and smartphone-powered “smart home” components.

Instead, Radio Shack chose to play little brother to Best Buy.

We can’t afford to repeat these mistakes with our own brands.

Each time we start to feel the urge to broaden our strategies and campaigns away from our ideal customer, we should return to a simple mantra: Specificity converts. Specificity converts. Specificity converts.

Even if you take nothing else away from Radio Shack’s story, remember this:

For any reasonable sample size, the specific offer to the specific person will always outperform the general offer to the general person.

You can follow Ken Bowen, Manager of Partner Content, MECLABS Institute, on Twitter at @KenBowenJax.

You might also like

Value Proposition: How to turn a shiny new value proposition into a high-performing page [MarketingSherpa webinar archive]

Marketing Optimization: 4 steps to discovering your value proposition and boosting conversions [More from the blogs]

Marketing Research Chart: Is value proposition testing part of your lead gen strategy? [MarketingSherpa chart]

Value Proposition: Between perception and reality [More from the blogs]