When testing to optimize a webpage, there are multiple metrics we track and a number of goals we strive to reach. However, the same two key performance indicators (KPIs) with accompanying goals always seem to pop up.

- Increase clickthrough – We want more people to like what they see on the page, click and go deeper into the funnel. People can’t convert if they don’t click.

- Increase conversion – We want people to absorb the information on the page and hope that it motivates them to ultimately convert.

An intuitive thought process follows that the more people click, the more people will convert.

In theory, if we optimize one KPI, the other will follow.

After a recent test we ran at MECLABS, however, I’d like to share with you how a decreasing clickthrough rate can actually be a good thing.

Setting the stage

After using our Conversion Heuristic to analyze one of our Research Partners’ pages and directly monitor consumer feedback, we were able to determine that visitors were asking for a comparison chart.

Our early analysis also suggested this to be a necessary piece for the landing page, as the only prior way to find this information was to click through and hunt around the site.

So, in order to match user motivation for visiting the page, we designed some treatments that included adding the comparison chart to the landing page.

We ran the test, collected our data, and then saw the results.

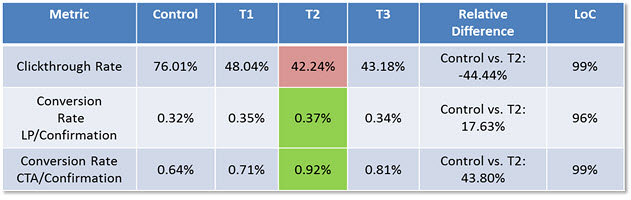

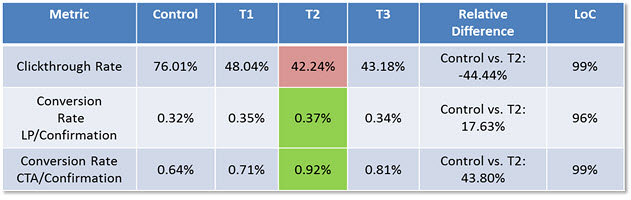

Our treatments decreased clickthrough by more than 40%.

Almost half of the people who would have clicked on the control did not click on our treatments.

This was not good – until we looked at our conversion rates.

For all three of our treatments, conversion increased significantly.

By now, you’re probably wondering how a decrease in traffic was also met with an increase in conversion, given the two metrics often seeming reliant upon each other.

The decrease in clickthrough can be attributed to two words: curiosity clicks.

Curiosity can inflate clickthrough rates

What do I mean by curiosity clicks?

Clickthrough traffic to the control was being artificially elevated because of these “curiosity clicks.”

These clicks came from people who were looking for information. They were curious and clicked through to look further for the information they wanted. Curiosity clicks can be a good thing and they can get people where you want them.

However, if clicking through to the next page still does not give the visitor the information they are looking for, they may exit the funnel altogether.

Our visitors were curious, clicked and were then probably disappointed not to find what they were looking for. On our treatment pages, they saw the information they were looking for directly on the landing page.

There was no need to move further into the funnel if that information didn’t suit their needs.

Turn up the dial on giving users the information they need

Although we can attribute curiosity clicks to explain our decrease in clickthrough, what about our increase in conversion?

By providing the comparison chart directly on the page, we prequalified those who were entering the funnel. They knew what they were getting into and made an informed decision to enter the purchase funnel.

Because of this, they were more likely to convert.

Ultimately, this increase in conversion also meant more revenue, so we were able to move past the decrease in clickthrough.

Related Resources

Online Testing: Microsite A/B split test increases lead rate 155%

Validity Threats: 3 tips for online testing during a promotion (if you can’t avoid it)

Online testing: Two common reasons to use a radical redesign test approach

Doesn’t the math point to Control winning? If 1000 visitors to control, 760 clicked through and 4.9 converted. Against T2, 420 clicked through and 3.9 converted. Unless cost is a factor in the clicks, I will keep running Control forever. What are we missing?

Hi,

Great question.

Cost per click can be a factor to consider in some tests, but in this particular experiment, the primary KPI was conversion rate.

When we looked at the data we found only 0.32% of traffic to the control page converted.

For visitors to the treatment 2 page, 0.37% converted, which resulted in a 17.63% lift.

Clickthrough was a secondary metric, and the decrease was interesting, but the point I wanted to drive here is that more clicks does not always mean more conversions as we discovered from this experiment.

Thanks,

Lindsay

Ahhh. We ecomm folks tend to think of clickthrough as coming from an external campaign such as email/social/display. If the clickthrough is from a page on site, then denominator of visitors or visits doesn’t change — Thanks for clarifying.

When a person first visits web page there are many factors that influence their decision to proceed. Top-selling salespeople get their customers thinking about the outcomes they desire. Very well said in this post. Thanks a lot Lindsay! Just about t time since I’m deciding to make changes to my website!

I got a bit confused. What exactly did you change about the control?

And how does “curiosity clicks” affect the clickthrough rate?