A recent question we received is a fairly common concern we hear from readers — customers only care about price — what do I do? So we’ve decided to answer it here on the MarketingExperiments Blog, since the answer might help you as well. And if you have a question you’d like answered on the blog, let us know.

Thanks for the outstanding workshop on value proposition. I agree that value propositions are the core to growth for any brand but the challenge I have is marketing products in a highly commoditized and fragmented category (olive oil). Price is such a dominant element of the value proposition that it’s difficult to compete unless you’re competitive on price, which is a no-win strategy. How have you seen other brands effectively create and market a value proposition that did not rely strongly on price? ”

– Brian

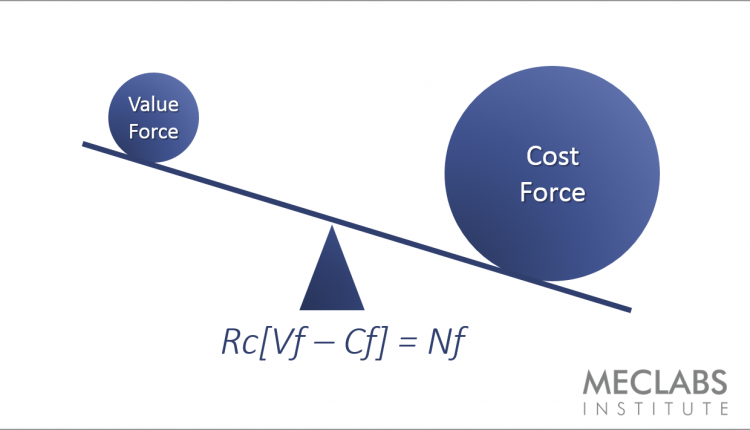

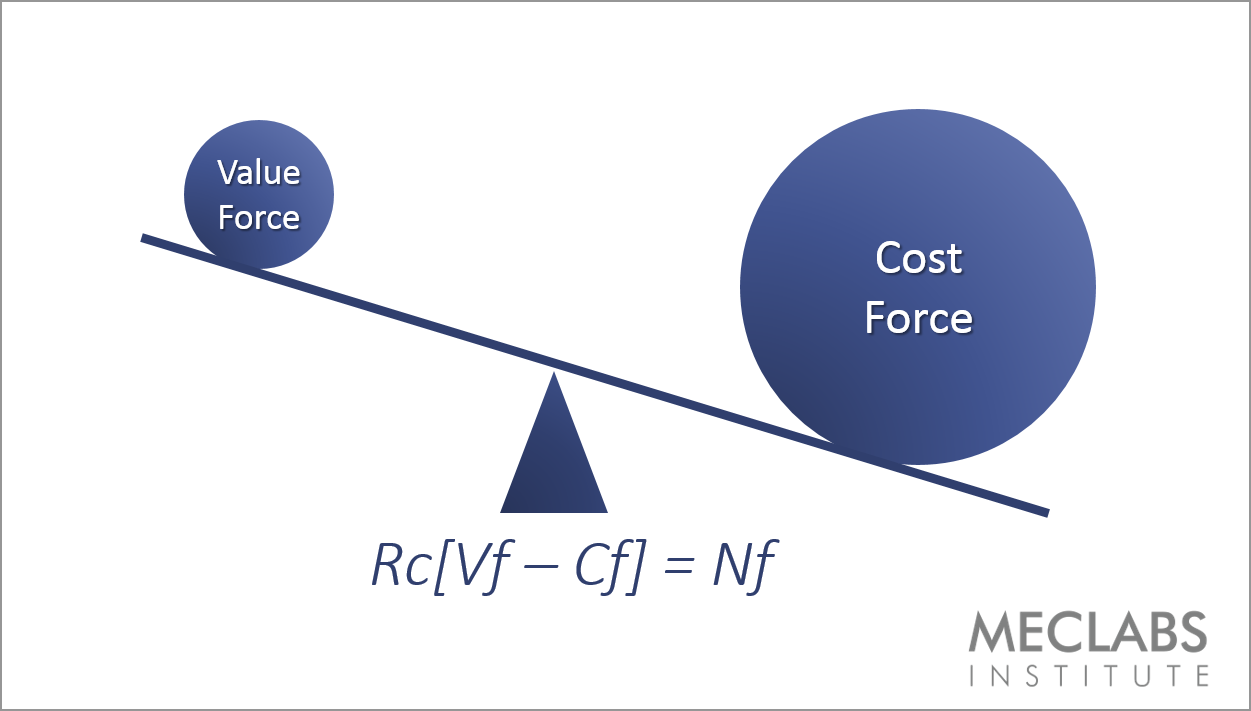

First, let me start by defining terms, which might help. Price is not an element of the value proposition. Price is part of the cost force of the buying decision.

For every purchase customers make, they weigh the cost against the value. If the cost is too high, they will not purchase. So, essentially, a company that does not have a strong enough value force (Vf) must reduce the cost force (Cf) to get the sale.

All that stands between you and the Barbarians at the gate is a good story

As Brian mentions, it is very difficult to succeed by selling on price alone. Mostly because you will be undercut. If you’re a retailer, you probably cannot sell cheaper than Wal-Mart and Amazon and still be profitable. And there are many overseas manufacturers who can undercut your price if your product becomes commoditized.

Much like the Roman Empire eventually lost its focus and was overtaken by the Barbarian tribes, these threats are always looming in the distance, waiting to strike when they see an opportunity. And your only protection is the value your product offers and the story you tell through your marketing to communicate that value.

As Marc Lobliner, CMO, Tigerfitness.com, told me, “Differentiate yourself on something no one can compete with. Not price. Someone will always be willing to make less money than you.”

So if you can’t decrease the cost force to get more conversions, you must increase the value force. This is where the value proposition comes in.

Wine is just old, expensive grape juice with a really good story

The value force is made up of appeal (I want this) and exclusivity (I can only get this from you).

So your first job is to create value in your product – appealing elements that have some level of exclusivity for your product. And then your next job is to tell that story well.

The questioner asked for effective examples of this. I think a good example that relates to olive oil is the wine industry.

Wine could be a commodity product. After all, it is just old grape juice. And you can buy wine at a low price point. For example, Charles Shaw is sold at Trader Joe’s for only a few dollars, earning it the nickname “Two Buck Chuck.”

However, you can also buy a bottle of Screaming Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon 2012 for $14,000.

Really, Charles Shaw and Screaming Eagle are not that different if you take the labels off the bottle. To a neophyte, they’re both mostly just aged, crushed up grapes with alcohol.

However, Screaming Eagle Winery and Vineyards has created an appealing, exclusive product for its ideal customer by producing small quantities of wines that have received 99 and 100 points from noted wine critic Robert Parker.

And that story is told well. In this case, because the value of the product is so strong, the story is coming less from the marketing and more from third parties. Listen to how wine critic Robert Parker makes the bottle sing, turning old grapes into a covetable $14,000 product: “The inky/purple-colored, seamless 2012 possesses an extraordinary set of aromatics consisting of pure blackcurrant liqueur, licorice, acacia flowers, graphite and a subtle hint of new oak.”

Building and communicating value

Robert Louis Stevenson said that “wine is bottled poetry.”

But olive oil is bottled poetry, too. And so is printer ink. And ketchup. Your job is to create that poetry and then write the poem through your marketing.

Let’s go back to olive oil. How can you increase the value force? How can you improve the value proposition?

Well, I did a quick search on Google Shopping for “olive oil,” and I can get a 25.5-ounce bottle of Bertolli Extra Virgin Olive Oil for $7.96 in a plastic bottle.

But if I search for “organic olive oil,” a 25.4-ounce bottle of Bionaturae Extra Virgin Olive Oil is $21 and comes in a glass bottle.

Aside from glass being a more appealing bottle than plastic, one of the reasons Bionaturae is able to charge three times more is simply because it is a USDA certified organic product. Organic increases the value force (for the ideal customer) because it taps into value that is appealing to the customer, such as the product is healthier or that it aligns with their values because synthetic chemicals were not used to grow the olives.

So the organic certification clearly adds some appeal but not much in the way of exclusivity. While organic olive oil is somewhat more exclusive than just plain olive oil, there are many brands of USDA certified organic olive oil. So let’s take a trip further up the price ladder.

One of the most expensive bottles of organic olive oil on the first page of my Google Shopping results is Minerva Olive Oil, which is $58 for 16.9 fluid ounces of olive oil. Like the Bionaturae, it has some of the same appeal because it is made from “100% organic olives that are pesticide and additive free.”

When I got to the Minerva Organic Extra Virgin Olive Oil landing page, additional elements of appeal are communicated. For example, it won a superior taste award.

But there are elements of exclusivity, as well. For example, it “arrives at your table after being thoroughly tested at Minerva laboratory, one of the 7 worldwide accredited laboratories by the International Olive Council.”

As you can see, I’m not just talking about marketing. And I’m certainly not talking about spin, hype or endless promotions. I’m talking about the creation of and then clear communication of value. This is why some wines sell for two bucks while other wine sells for $14,000 – and why some customers will pay $7.96 for olive oil, while others will pay $58.

How to uncommoditize your products

Sure, it’s not a word, but I say if products can be commoditized, you should be able to uncommoditize them as well. If you’ve decided that your business strategy is not to compete on price, here are a few ideas to help you build that value proposition.

Step #1. Identify the ideal customer

Some people will never spend $58, or even $21, for a bottle of olive oil. They’ll spend $7.96 every single time.

And that’s fine. However, it doesn’t mean you have to compete on price.

You can identify customers that are willing to spend a little or a lot more for your product than the base price and understand what they value.

Step #2. Identify the value your product already offers

Fingers crossed here – but your product already offers some value to the world. It may just be a base level of value that corresponds to the commoditized price for that product.

Or, you may be offering additional value that you aren’t communicating. For example, many customers now place a significant value on how their food is produced. If you’re producing olive oil grown by family farmers in California from olive trees planted 100 years ago but you’re not communicating it to your customers, there may be hidden value that you can reveal with your marketing to increase the value force to your customers.

Step #3. Identify the value your product could offer

Again, increasing the price of your product takes more than marketing. You must increase the tangible and intangible value of your product and then increase the perception of that value with your marketing.

For example, let’s say you discover that your ideal customer is worried about inferior quality olive oil being passed off as extra virgin olive oil. You could contract with a third-party service, perhaps a local university, to run tests and certify that your olive oil is the real deal.

This is combining the tangible value your product already had (you’ve always been selling the good stuff) with intangible value (the third-party verification) to create greater perceived value and a stronger value force.

Step #4: Turn actual value into perceived value

The actual value of your product has no value force until your customers perceive it. And this is where your marketing comes in.

Create content marketing that tells the story of the farmers growing the olives for your oil. Use a third-party seal to show that your olive oil is the good stuff. Use your marketing to help customers clearly understand the value of your product.

And then — and only then — can you increase the price.

You can follow Daniel Burstein, Director of Editorial Content, MECLABS Institute, @DanielBurstein.

You might also like

Value Proposition Development online course [From MECLABS, parent research organization of MarketingExperiments]

Content Marketing: How a farm justifies premium pricing [From MarketingSherpa Blog]

Marketing Strategy: What is your “Only Factor”? [From MarketingSherpa Blog]

MarketingExperiments Research Directory

Consumer Marketing: All that stands between you and Walmart is a good story

This is absolutely top notch advice!

Nailed it perfectly – and with engaging style too.

As an actual wannabe buyer of olive oil, I simply quit buying it because so often it tasted different. One bottle I bought very obviously tasted of linseed oil! About the ONLY thing that would get me buying is a 3rd party endorsement and proof of it being genuine – and even then I’d want something easily checked online. A possible business opportunity for someone? Essential oil companies face the same problem.

I don’t usually bother to post just to clap and say bravo, but this deserves one – bravo!