Want to know the secret to always running successful tests?

The answer is to formulate a hypothesis.

Now when I say it’s always successful, I’m not talking about always increasing your Key Performance Indicator (KPI). You can “lose” a test, but still be successful.

That sounds like an oxymoron, but it’s not. If you set up your test strategically, even if the test decreases your KPI, you gain a learning, which is a success! And, if you win, you simultaneously achieve a lift and a learning. Double win!

The way you ensure you have a strategic test that will produce a learning is by centering it around a strong hypothesis.

So, what is a hypothesis?

By definition, a hypothesis is a proposed statement made on the basis of limited evidence that can be proved or disproved and is used as a starting point for further investigation.

Let’s break that down:

It is a proposed statement.

- A hypothesis is not fact, and should not be argued as right or wrong until it is tested and proven one way or the other.

It is made on the basis of limited (but hopefully some) evidence.

- Your hypothesis should be informed by as much knowledge as you have. This should include data that you have gathered, any research you have done, and the analysis of the current problems you have performed.

It can be proved or disproved.

- A hypothesis pretty much says, “I think by making this change, it will cause this effect.” So, based on your results, you should be able to say “this is true” or “this is false.”

It is used as a starting point for further investigation.

- The key word here is starting point. Your hypothesis should be formed and agreed upon before you make any wireframes or designs as it is what guides the design of your test. It helps you focus on what elements to change, how to change them, and which to leave alone.

How do I write a hypothesis?

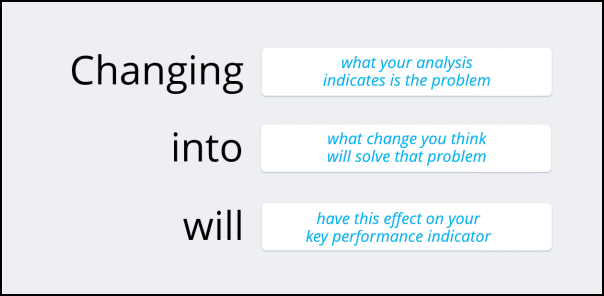

The structure of your basic hypothesis follows a CHANGE: EFFECT framework.

While this is a truly scientific and testable template, it is very open-ended. Even though this hypothesis, “Changing an English headline into a Spanish headline will increase clickthrough rate,” is perfectly valid and testable, if your visitors are English-speaking, it probably doesn’t make much sense.

So now the question is …

How do I write a GOOD hypothesis?

To quote my boss Tony Doty, “This isn’t Mad Libs.”

We can’t just start plugging in nouns and verbs and conclude that we have a good hypothesis. Your hypothesis needs to be backed by a strategy. And, your strategy needs to be rooted in a solution to a problem.

So, a more complete version of the above template would be something like this:

In order to have a good hypothesis, you don’t necessarily have to follow this exact sentence structure, as long as it is centered around three main things:

- Presumed problem

- Proposed solution

- Anticipated result

Presumed problem

After you’ve completed your analysis and research, identify the problem that you will address. While we need to be very clear about what we think the problem is, you should leave it out of the hypothesis since it is harder to prove or disprove. You may want to come up with both a problem statement and a hypothesis.

For example:

Problem Statement: “The lead generation form is too long, causing unnecessary friction.”

Hypothesis: “By changing the amount of form fields from 20 to 10, we will increase number of leads.”

Proposed solution

When you are thinking about the solution you want to implement, you need to think about the psychology of the customer. What psychological impact is your proposed problem causing in the mind of the customer?

For example, if your proposed problem is “There is a lack of clarity in the sign-up process,” the psychological impact may be that the user is confused.

Now think about what solution is going to address the problem in the customer’s mind. If they are confused, we need to explain something better, or provide them with more information. For this example, we will say our proposed solution is to “Add a progress bar to the sign-up process.” This leads straight into the anticipated result.

Anticipated result

If we reduce the confusion in the visitor’s mind (psychological impact) by adding the progress bar, what do we foresee to be the result? We are anticipating that it would be more people completing the sign-up process. Your proposed solution and your KPI need to be directly correlated.

Note: Some people will include the psychological impact in their hypothesis. This isn’t necessarily wrong, but we do have to be careful with assumptions. If we say that the effect will be “Reduced confusion and therefore increase in conversion rate,” we are assuming the reduced confusion is what made the impact. While this may be correct, it is not measureable and it is hard to prove or disprove.

To summarize, your hypothesis should follow a structure of: “If I change this, it will have this effect,” but should always be informed by an analysis of the problems and rooted in the solution you deemed appropriate.

Related Resources:

A/B Testing 101: How to get real results from optimization

15 Years of Marketing Research in 11 Minutes

Marketing Analytics: 6 simple steps for interpreting your data

Website A/B Testing: 4 tips to beat an unbeatable landing page

Thanks for the article. I’ve been trying to wrap my head around this type of testing because I’d like to use it to see the effectiveness on some ads. This article really helped. Thanks Again!

Hey Lauren, I am just getting to the point that I have something to perform A-B testing on. This post led me to this site which will and already has become a help in what to test and how to test .

Again, thanks for getting me here .

Lance

Good article. I have been researching different approaches to writing testing hypotheses and this has been a help. The only thing I would add is that it can be useful to capture the insight/justification within the hypothesis statement. IF i do this, THEN I expect this result BECAUSE I have this insight.

@Kaya

Great!

Good article – but technically you can never prove an hypothesis, according to the principle of falsification (Popper), only fail to disprove the null hypothesis.