When it comes to website testing, maybe you’ve heard of the terms type I and type II errors, but never really understood what they mean.

Perhaps you’re thinking they might have something to do with personality types, like a type I personality that is perhaps more aggressive than a type II personality. Or maybe blood type comes to mind?

These are, of course, all wrong.

In the context of testing, what we are really referring to are type I and type II statistical errors. These are concepts that two prominent statisticians, Jerzy Neyman and Egon Sharpe Pearson, first developed in the 1930s (which are great names by the way – makes me picture a Hell’s Angel and a Ghostbuster teaming up to do some stats).

Here’s how these errors are commonly defined in statistics:

- Type I: Rejecting the null hypothesis when it is in fact true.

- Type II: Not rejecting the null hypothesis when in fact the alternate hypothesis is true.

Anuj Shrestha, a fellow data scientist at MECLABS, had a great interpretation for these concepts: “Type I is sending an innocent person to jail and type II is letting a guilty person go.”

Most people would probably agree that sending an innocent person to jail is much more egregious than letting a guilty person walk. When it comes to making business decisions based on website testing, the equivalent is also true.

It is arguably much more damaging to make a decision based on a false positive – for example, pushing a webpage live that you incorrectly believe performed better than an alternative – versus a false negative, which is like declaring that treatments were not statistically different from one another when they were, resulting in a missed opportunity.

For this reason, we will focus on a few specific scenarios concerning type I errors to put this concept into perspective.

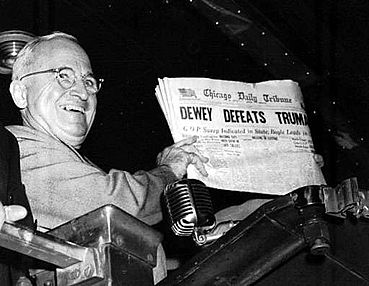

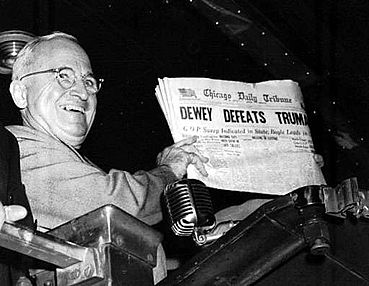

The Chicago Tribune and Gallup accidentally defeat Truman

One of the most famous examples of a type I error in politics involved pollsters and the Chicago Tribune during the 1948 presidential election. At the time, the accepted sampling methods in polling were not as refined as they are today.

One of the most famous examples of a type I error in politics involved pollsters and the Chicago Tribune during the 1948 presidential election. At the time, the accepted sampling methods in polling were not as refined as they are today.

Non-random sampling, coupled with ending polling prematurely before a representative sample was collected, led pollsters to incorrectly conclude that Thomas E. Dewey would defeat Harry S. Truman.

Based on this information, the Tribune’s headline declaring Dewey the victor was a huge blunder and was forever captured in the famous photograph of Truman holding a copy of the Tribune next to his gigantic smile.

Pollsters and the Tribune committed a type I error by stating Dewey would win (a false positive) when in fact, he did not.

Error always has a slim chance

Relating this idea to website testing, consider what a type I error would mean to a hypothetical homeowners insurance company.

Say you are in charge of testing a page and want to know if adding copy expressing urgency would significantly increase conversions compared to copy with a few concise value points.

The urgency treatment includes copy telling prospects to “Click now before it’s too late and you lose your home, your job and all of your friends!”

The value copy treatment instructs prospects on the benefits of purchasing homeowners insurance, stating, “Purchasing homeowners insurance protects you and your loved ones from disaster and provides peace of mind.”

Traffic is split between these two treatments and the data rolls in.

Lo and behold, you find that the conversion rate for the urgency treatment destroys the value copy treatment at a 95% level of confidence. Hurray! You have a winner, and you push the urgency treatment live.

A week later, you see a crazy drop in conversions. Another week goes by and conversions stay consistently low. Could it be that you’ve committed a type I error?

That is the gamble.

The test validated at a 95% level of confidence, which sends high fives all around, but the dark side of testing that people don’t always pay attention to is that a 95% level of confidence means you are willing to accept the small chance that five times out of 100, you will commit a type I error.

The odds are low, but it can happen.

So understand that the possibility of a type I error is ever-present. The best that we can do to mitigate this chance is to follow the principles of scientifically rigorous test designs that hopefully limit the validity threats that can send your winning page to the slammer.

Photo attribution: Associated Press

You may also like

Can I Test More Than One Variable at a Time? [Video]

Interpreting Results: Absolute difference versus relative difference

Web Analytics: What browser use can tell you about your customers

Analytics and Testing: Understanding statistics symbols and terminology for better data analysis